A play on the doubled chromosome and subversive of the commonplace glib male evaluation of women’s ‘x factor’, THE XX FACTOR is a lively, challenging and satisfying mix of moving image, photography and painting by noted international and New Zealand artists. Two X chromosomes speak volumes: through millennia, they have delivered the realities and rigours and flights of imagination of roughly half of humankind, encompassing biology and the socio-cultural norms and particularities of each era / place. Trish Clark’s unexpected grouping of artists illuminates their commonalities, across continents and oceans, time and individual paths.

In Marina Abramović’s seminal 1976 work, Freeing the Memory, the artist’s face is full frame: reciting all the words in her memory like a mantra – at once reflecting her particular woman’s experience, the constant cadence of the words giving the work a sustained trance-like intensity, while attempting to reach a higher level of consciousness.

Alexis Hunter was a 70’s pioneer in her focus on the female gaze directed outward, articulating a sense of liberty while being remarkably prescient in her understanding of the extreme manipulation of the consumer that would saturate the world with sexual visual language. Embracing the era’s new technologies, her images are eloquent harbingers of our Instagram era.

A highly complex depiction of female-male relationships using the simplest of forms and hypnotic rhythm by Spanish artist Pilar Albarracín in her film, I Will Dance On Your Grave, was included in the 2005 Venice Biennale by Rosa Martinez. Consistently undermining dominant narratives, and positing herself as protagonist, Albarracín’s films pierce the comfort of her homeland’s populist identity politics.

Carolee Schneemann, pioneer in discourse on the body, sexuality, and gender, features with her seminal self-shot mid-60’s film Fuses, a transfixing study of female-male physical relationship. Recognizing early on that “the brush belonged to abstract expressionist male endeavor” Schneemann turned to strongly experimental film and performance, seeking always to address “where the taboos and censorious conventions are embedded aesthetically” and express her own sexuality outside the ambit of male power and gaze.

Heather Straka has long challenged, with sly wit, prevailing norms of sexuality and commerce and their intermingling. Working in series, time and again she confounds stereotypical readings of particular cultural practices. These new works, alluring in their lush painterliness and coy beauty, issue a siren’s call, and hint at the complexity and dangers that lurk concealed there.

More directly, Julia Morison’s Centrefolds (made in 2000 and exhibited in the 2nd Auckland Triennial at Auckland Art Gallery) utilize ‘dragon’s blood’, ink and pastel worked onto old European Bible paper (unstitched by the artist) in remarkably vulval Rorschachs that amplify and confound the relative values and merits of faith-based systems and the sanitized prurience of ‘men’s magazines’ – those coy artefacts of yesteryear before the onslaught of hardcore internet porn – while referencing the 70’s predilection for inspecting one’s own vulva as a mark of liberation.

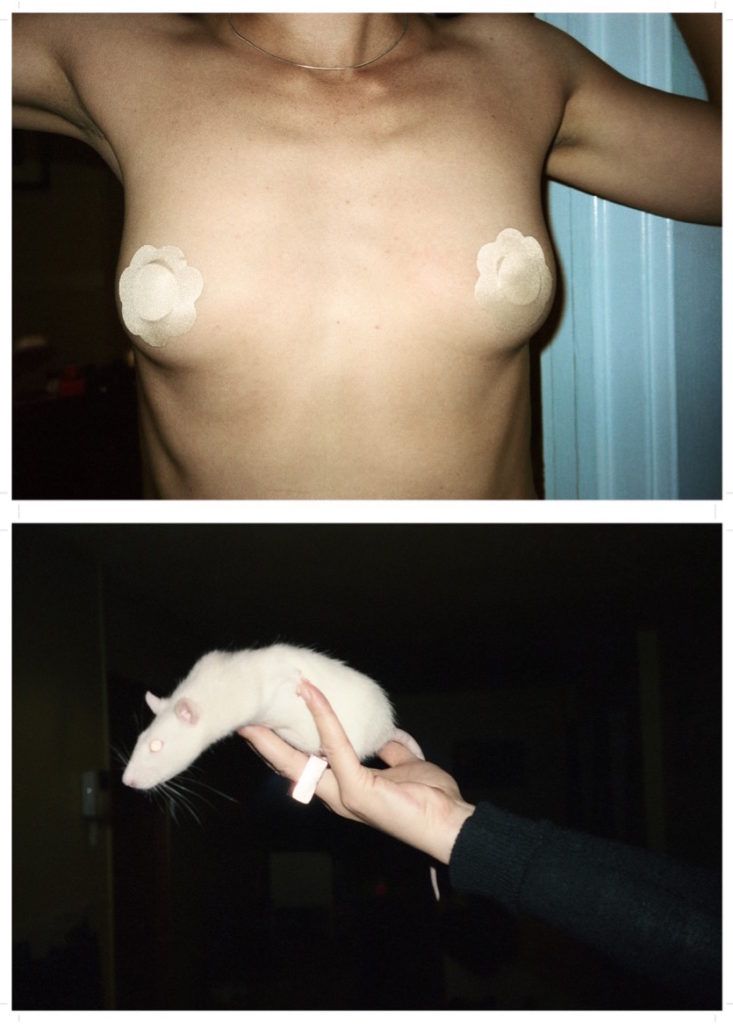

A very different Pussy emerges in Marie Shannon’s troika of new works. Shannon’s signature playfulness of expression is at once questioning and knowing, direct and sly; her subject objects both mundane and evocatively profound.

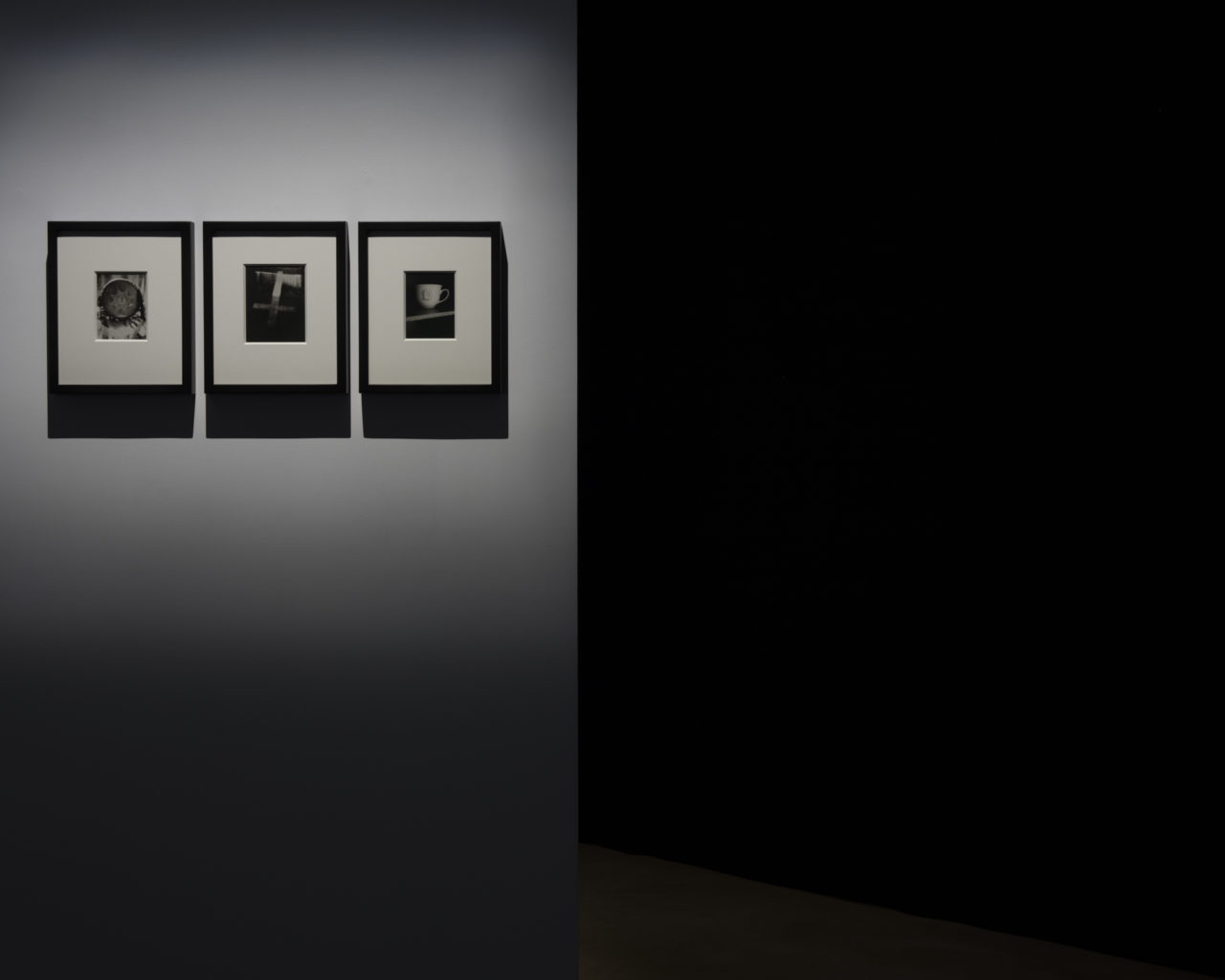

Punk goddess Patti Smith has maintained a private photographic practice since the 1970’s, ‘based more on meditation than observation.’ More publicly accessible of recent years, her silver gelatin photographs are sensitively captured sites and objects of personal significance, at once delicate and extraordinarily expressive, ‘containing all that I understand about light and composition.’

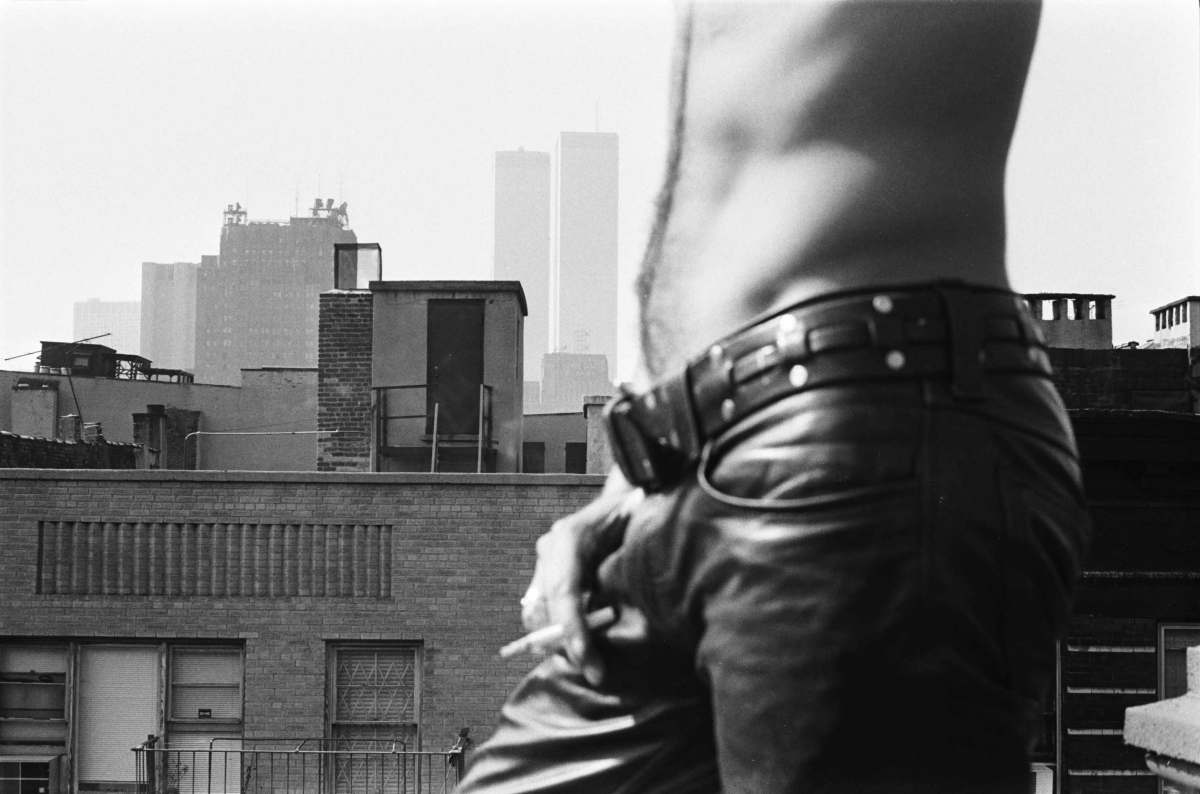

Ann Shelton, subject of an upcoming mid-career survey at Auckland Art Gallery November 2016 – April 2017, has consistently operated at the nexus of conceptual and documentary modes of photography. Her series Erewhon captures spaces and people ‘in-between’: in between the public and the deeply personal, the familiar and the confrontational, the deeply banal and the dangerous.

Continuing this interplay Christine Webster’s works from Blindfield reveal the shadow of a common presentation of the female being, evoking an unnerving treatise on ‘hysteria’ and the normalization of damaging semiotics that an entire gender has been subjected to; an at once shared and private despair.