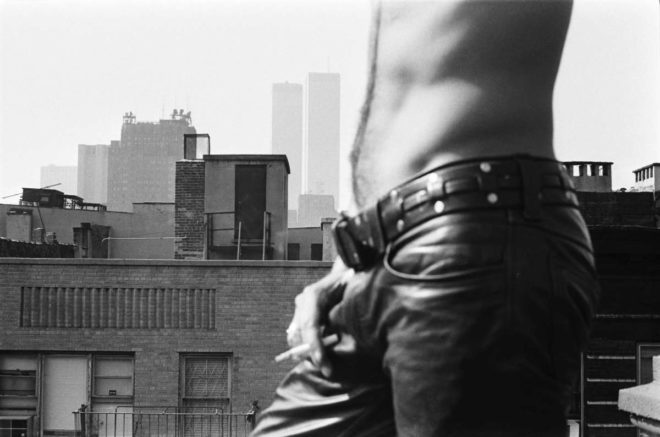

Critic Lucy Lippard noted of Alexis Hunter: “Fetishism and a hint of S&M lurk just beneath the surfaces of Hunter’s photographs … Her rage at capitalism is focused upon the mass media which have, as Judith Williamson puts it, been ‘selling us ourselves’ for profit.”

The titles of Alexis Hunter’s works of art are pointed: Approach to Fear; Voyeurism; Violence: Destruction of Evidence; Identity Crisis; Effeminacy; Sexual Warfare; Masculinisation of Society; Oh No!; Dialogue with a Rapist. These were the ideas and themes that preoccupied her, explored from the 1970s onwards in a series of conceptual works using photography, film and text. Her iconic image sequence of her hands burning silver platform shoes, Approach to Fear XIII: Pain – Destruction of Cause 1977, was acquired by Tate in 2013, shortly before her premature death from motor neurone disease in 2014.

Alexis Hunter was born in New Zealand and, after graduating with Honours in painting and History of Art and Architecture from The University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Art in 1969, travelled to London where she joined the Women’s Workshop of the Artists Union while working in commercial film and animation. The Narrative Sequences were devised as an intervention in the women’s art movement of the seventies and at the time was shown at the Hayward, the ICA and the Sydney Biennale and various European museums. With renewed interest in the work it was shown in ‘Live in Your Head: Concept and Experiment in Britain’ at the Whitechapel Gallery, London; ‘Work’ at Taxi Palais, Innsbruck; ‘WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution’ at MCA, Los Angeles. Lynda Morris of the Norwich Gallery curated a large exhibition of this sequential work ‘Alexis Hunter: Radical Feminism in the 1970s’, which travelled to Bunkier Sztuki, Kracow, Poland. During the 1980’s Hunter became Visiting Lecturer at the School of Visual Arts, New York and Byam Shaw in London, then Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Houston, Texas. She also curated various exhibitions on painting and politics.

Hunter focused on the female gaze, with images that articulated a sense of liberty at odds with the predominant masculinity of the era expressed confidently in politics, public, and media – print and electronic. Hunter’s images were also prescient in their understanding of the extreme individuation and manipulation of the consumer now saturating the world with sexual visual language. Her particular form of imagemaking opens up thinking about the intersection of feminism, new technologies, and a disruptive epoch. Experimenting with the new media of the time, Hunter’s images foreshadowed how technologies now mediate our desires and inner thoughts: they are eloquent harbingers of our Instagram era.